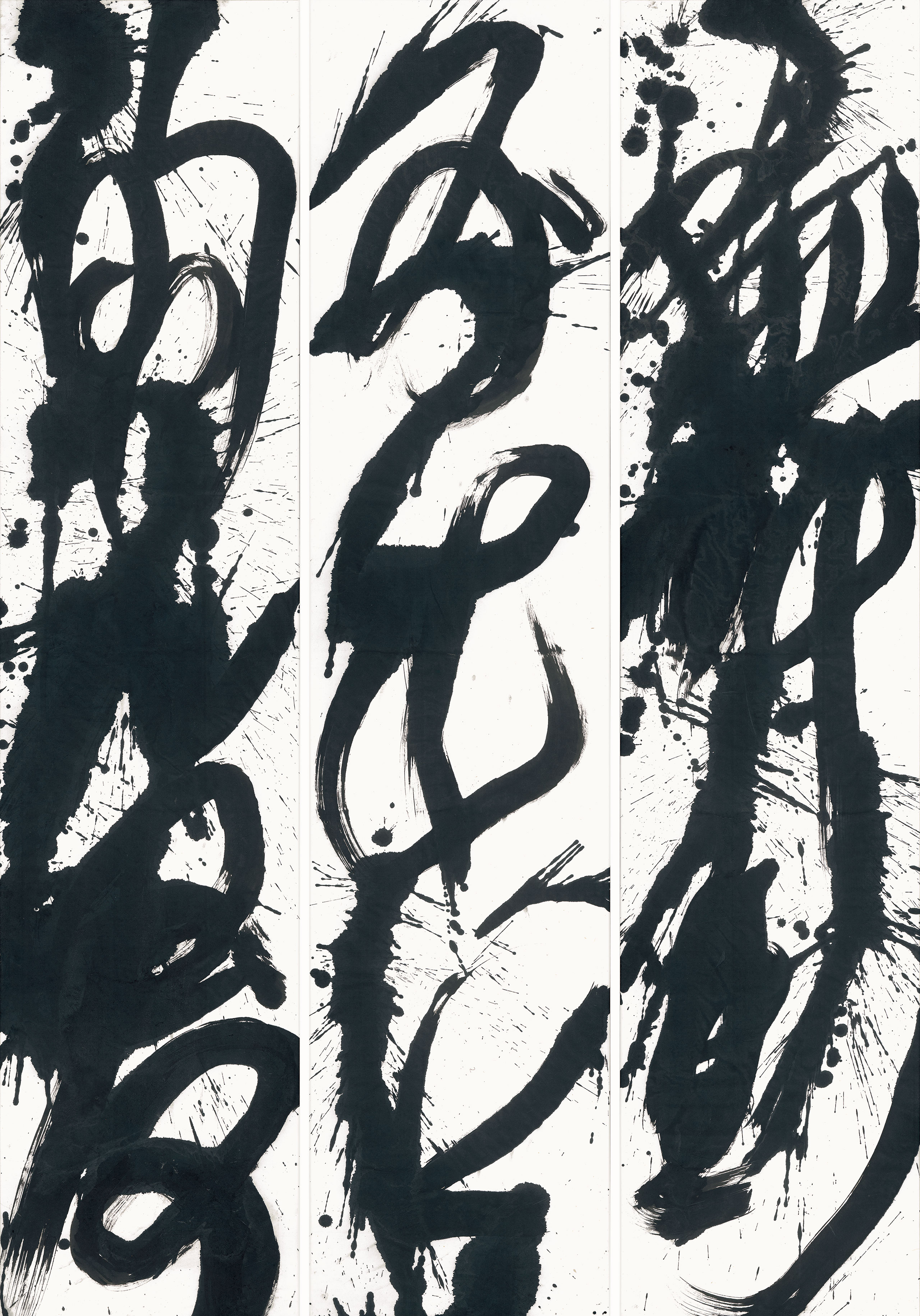

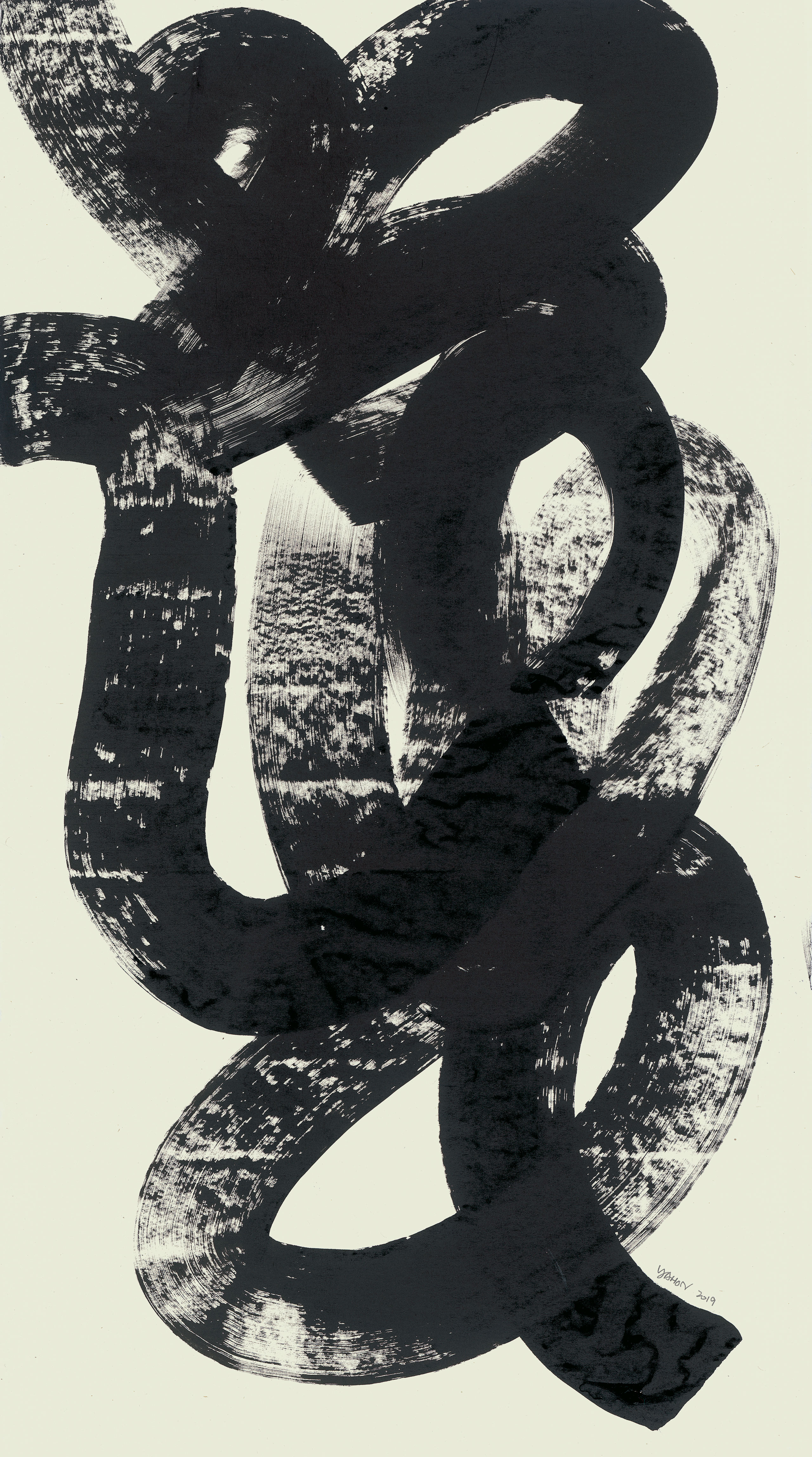

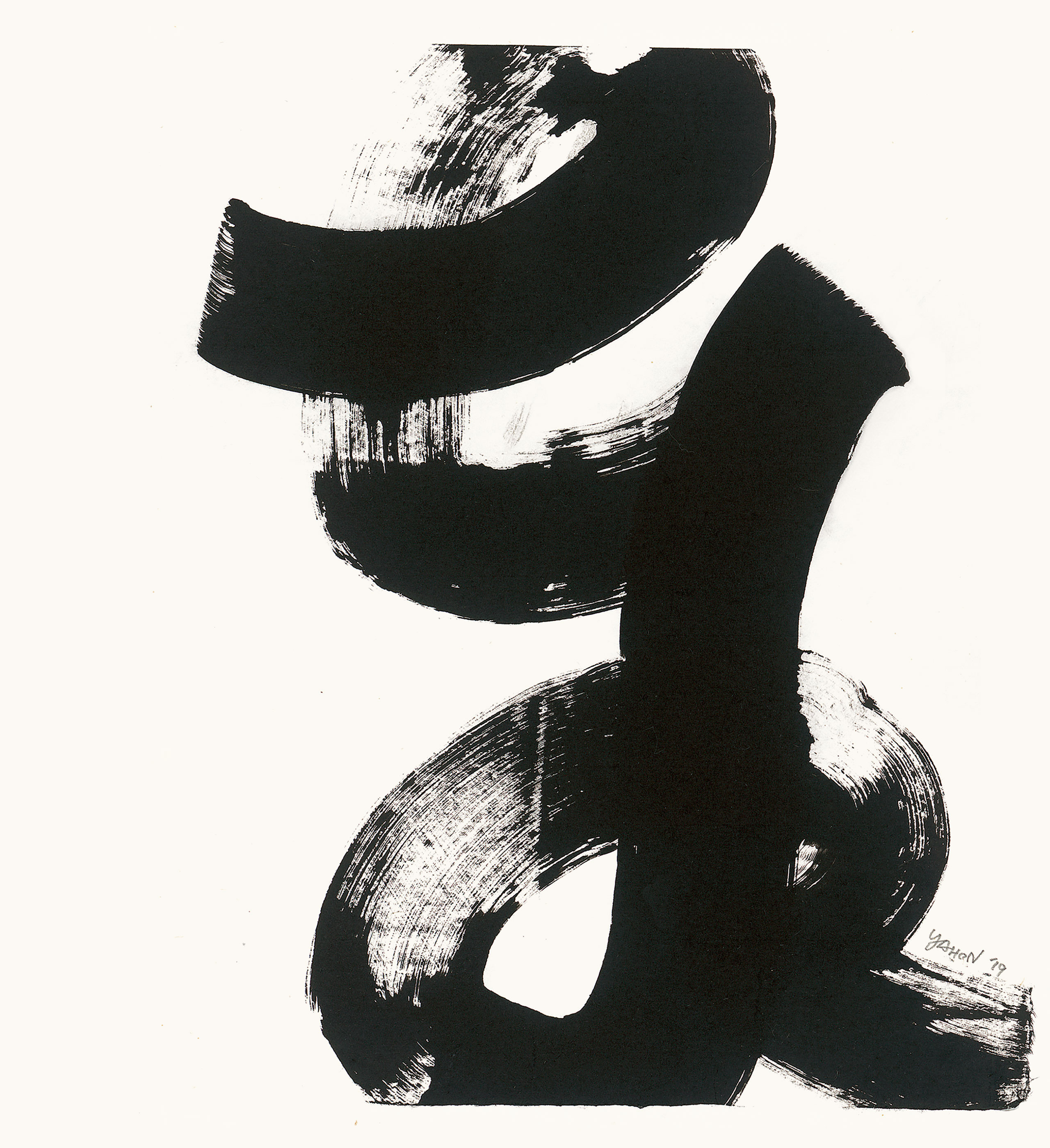

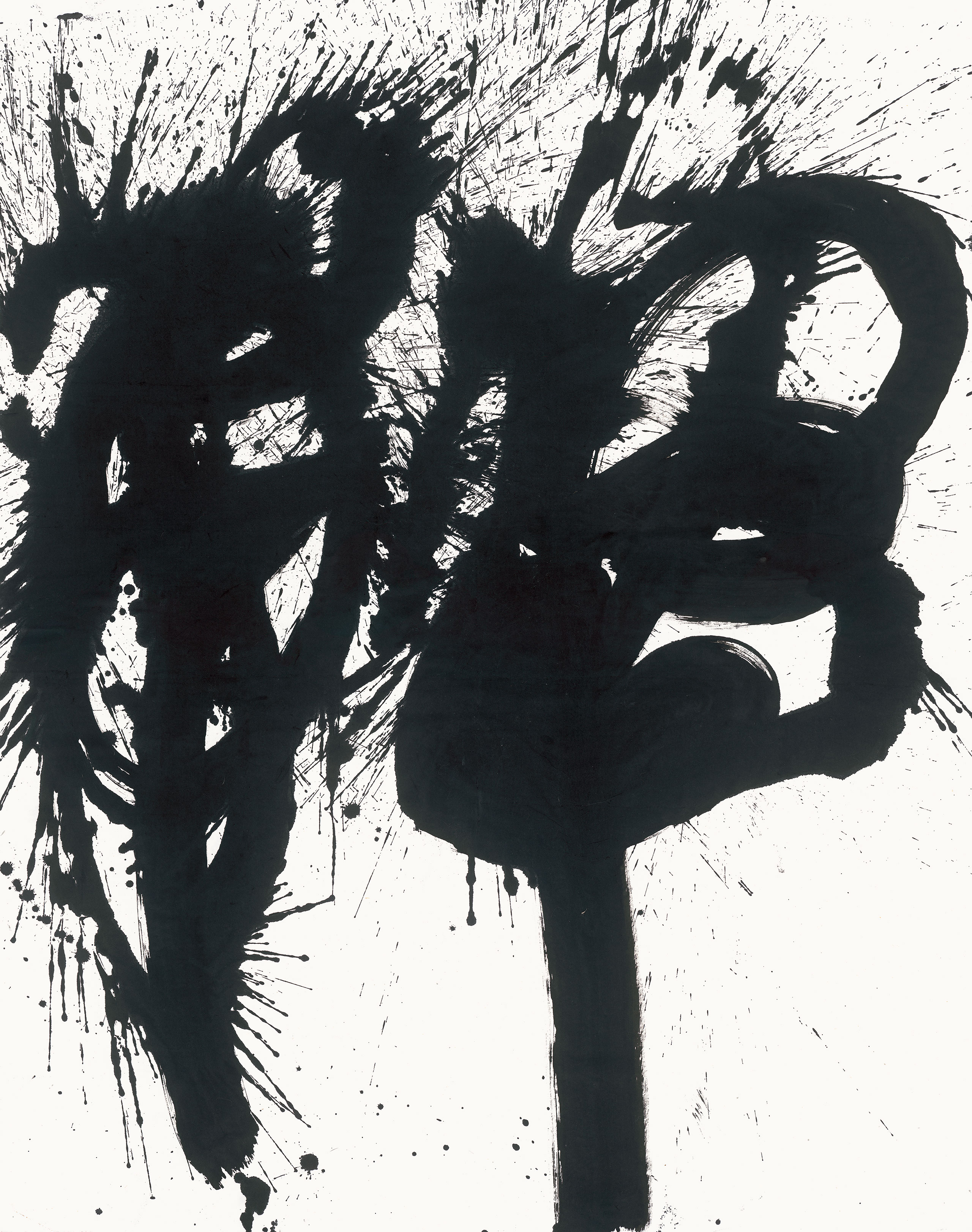

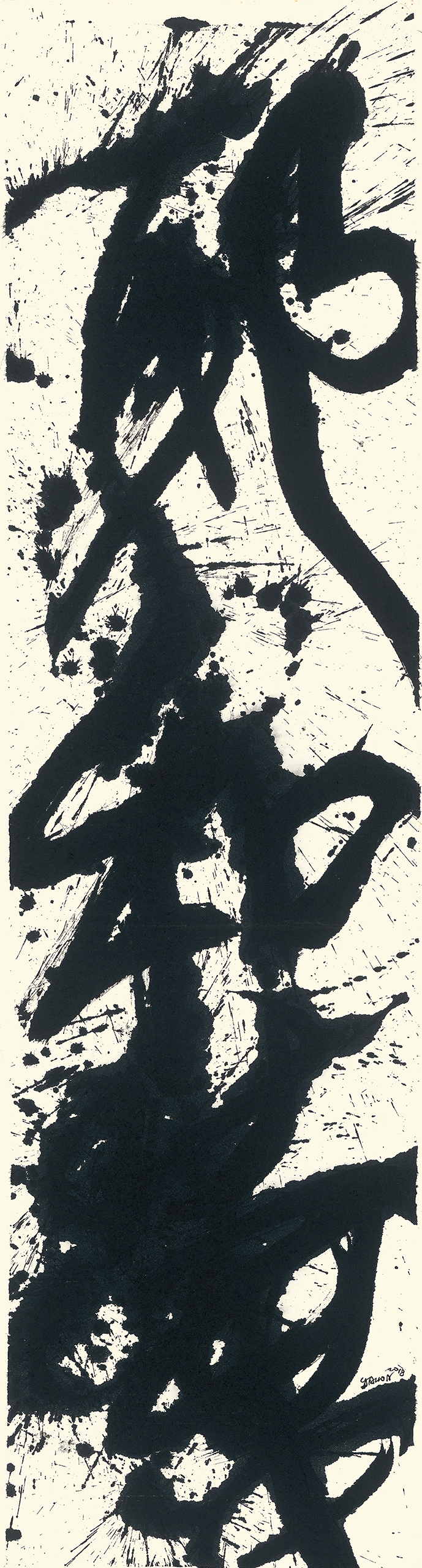

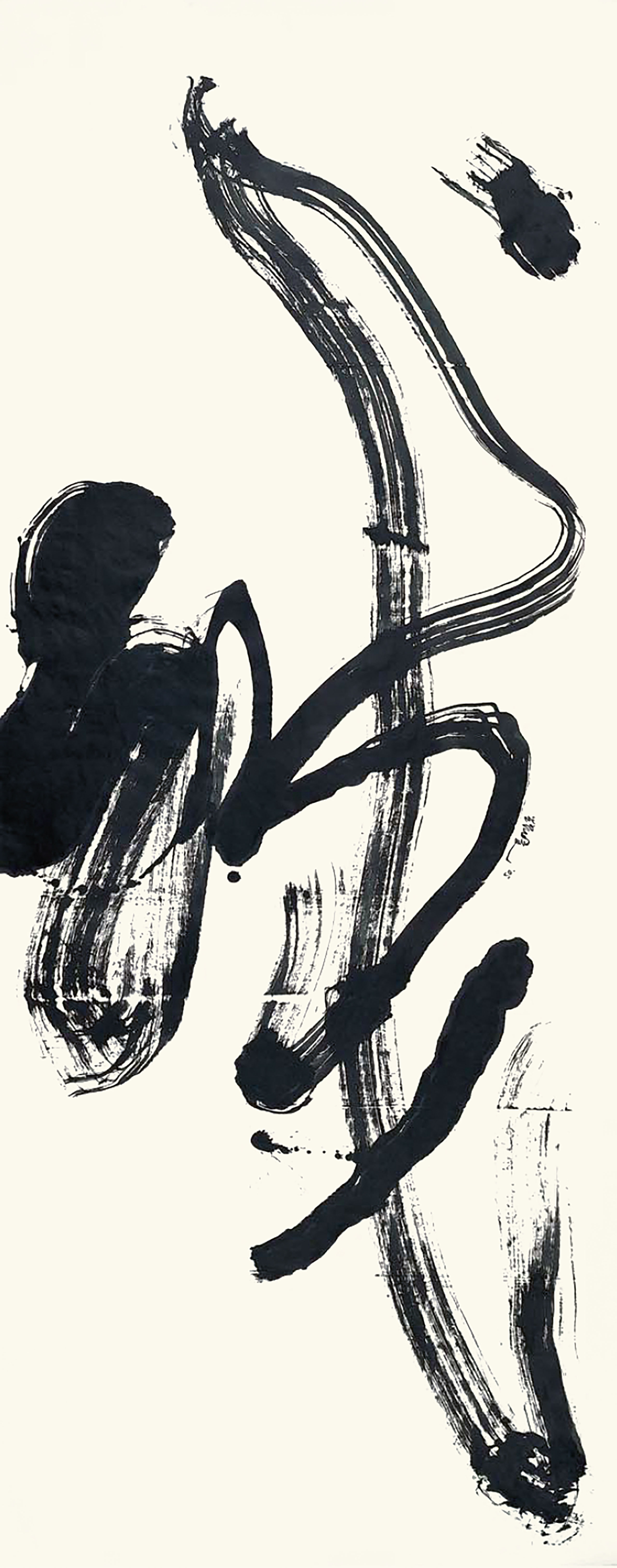

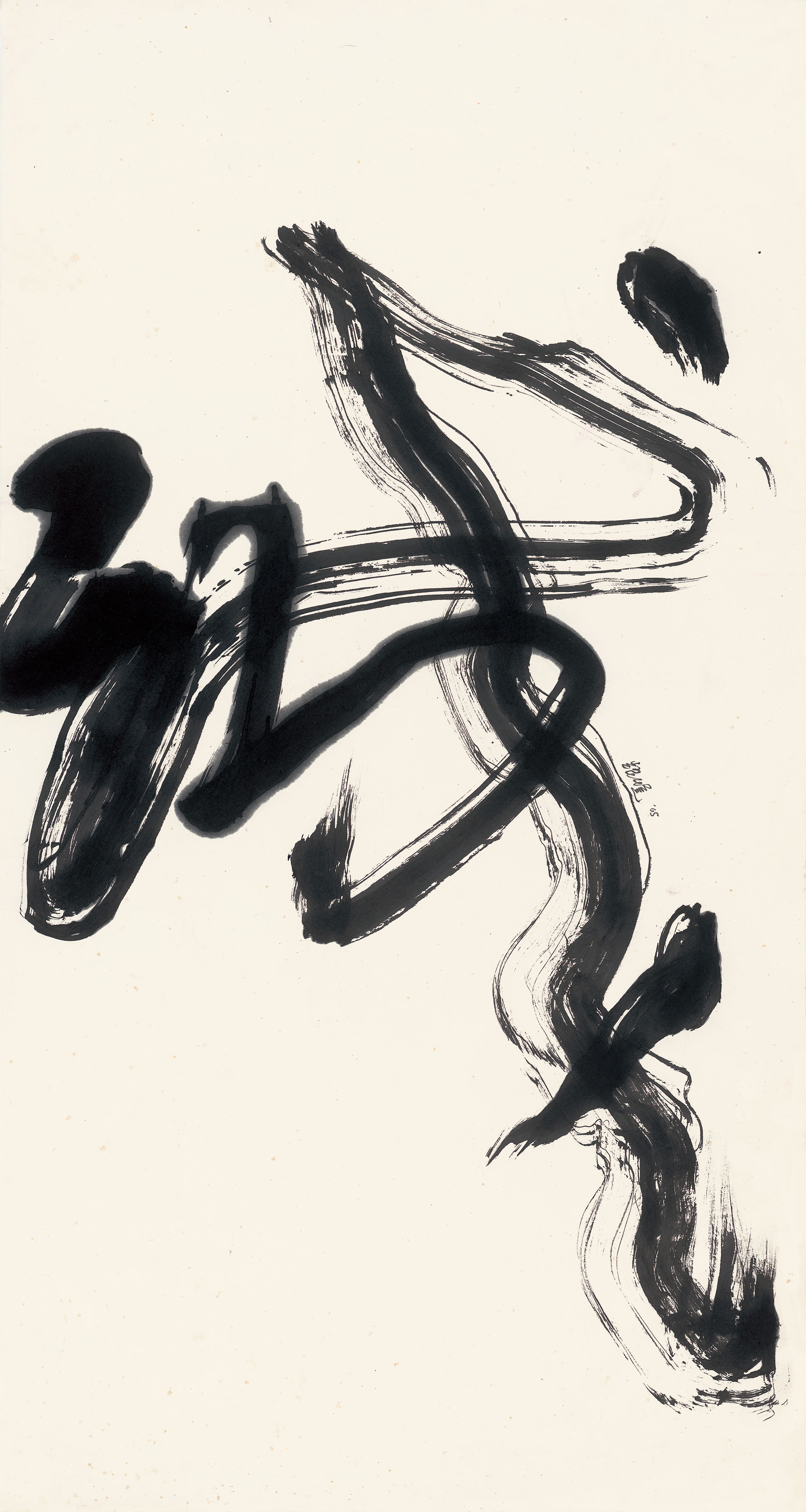

Calligraphy (1988–present)

For over a thousand years, calligraphy has been considered one of the most elite forms of Chinese art, with decades of training necessary to attain the zenith of the practice. Yahon Chang, for example, began his lifetime of study at the age of six. Most of the thousands of characters, or graphs, have a complex composition, with many variants, but the overriding goal lies not in memorization, but in laying down motor memory through repetitive writing. With such mastery, the artist has no need to consider how to write a given text: with no conscious effort it simply flows from mind to body to brush to paper. Most importantly, calligraphy is revered as a direct expression of the writer’s persona in the moment. The characters serve as vehicles for the transmission of the artist’s qi, or life breath.

— Britta Erickson